Study quantifies human fecal pollution in urban stormwater

SCCWRP and its partners have completed a sweeping, five-year investigation quantifying the relative contributions of six major sources of human fecal contamination in the San Diego River watershed during wet weather – a multicomponent scientific undertaking that has produced groundbreaking insights into one of the most vexing challenges in stormwater management.

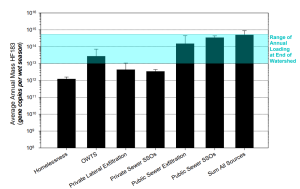

The first-of-its-kind study, summarized in a technical report published in June, found that public sewer overflows, exfiltration from public sewers, and onsite wastewater treatment systems are the three largest contributors to human fecal contamination measured at the end of the highly urbanized San Diego River watershed

People experiencing homelessness contribute the smallest fraction of human fecal contamination, followed by private sewer overflows and exfiltration from private laterals.

The study in San Diego provides the most comprehensive insights to date into among the toughest, most complex questions confounding Southern California’s water-quality management community: What are the major sources of human fecal contamination found in urban waterways and beaches during wet weather?

For years, managers have been finding elevated levels of human fecal contamination in Southern California wet-weather runoff, but the study in San Diego marked the first time that researchers had attempted to systematically tease apart the relative contributions of each of six major hypothesized sources human inputs. The study took advantage of recent scientific advances; researchers also developed and piloted novel scientific methods to support the study.

While the study produced groundbreaking insights for one Southern California watershed, it remains unclear how broadly applicable the study’s findings are to other watersheds; the relative contributions of each of the six major fecal sources could be different in different watersheds. With the study’s completion, San Diego River watershed managers are now poised to focus on deciding how best to mitigate each of the six major sources of human fecal contamination, including deciding how to prioritize and allocate resources among them.

The study also paves the way for more focused follow-up investigations that could help confirm some of the study’s key findings, including explaining the specific routes and mechanisms by which some of the human fecal contamination could be transported to the San Diego River during wet weather.

In particular, researchers are interested in understanding how sewage that has leaked from public and private sewer systems travels underground to reach surface waters. Improved understanding of these subsurface transport mechanisms also could increase managers’ confidence about what actions to take in response to the investigation’s findings.

One of the novel source-tracking approaches that researchers piloted during the study is the use of biofilms to link fecal contamination in the watershed to sanitary sewer pipes. The term biofilm refers to the unique microbial community that lines the inside of sewer pipes. When researchers find the genetic signature of sewer biofilm in stormwater runoff, it provides confirmation that human sources of fecal contamination originated in sanitary sewer pipes.

During the study, researchers also developed a prototype method for detecting leaks in underground sewer pipes. Researchers found that the sewer exfiltration measurement method – which targets specific segments of pipes – has the potential to be useful for detecting very small amounts of exfiltration that may evade detection during traditional camera-based inspections.

The study in San Diego involved quantifying human fecal contamination levels using HF183, a genetic marker found only in human feces. HF183 is a more specific, more sensitive indicator of human fecal contamination than traditional fecal indicator bacteria such as E. coli or Enterococcus, which can be shed from any warm-blooded animal, including dogs, birds and other wildlife.

The study found that the cumulative HF183 contribution from the six measured human fecal sources is consistent with the HF183 levels independently measured at the end of the San Diego River watershed, indicating that the study successfully accounted for all major contributors to human fecal pollution.

The study was guided by a steering committee made up of representatives from San Diego stormwater and wastewater agencies, the San Diego Regional Water Quality Control Board, and environmental NGOs. A technical review committee consisting of six national science and engineering experts vetted the study’s technical approach and conclusions.

The investigations targeting each of the six major fecal pollution sources are expected to be published as standalone manuscripts in peer-reviewed journals. The work to quantify the contributions from unhoused populations was already published earlier this year. Meanwhile, manuscripts on the sewer exfiltration measurements and onsite wastewater treatment system work have already been submitted to scientific journals.

For more information, contact Dr. Joshua Steele or Ken Schiff.

More news related to: Microbial Source Tracking, Microbial Water Quality, Top News